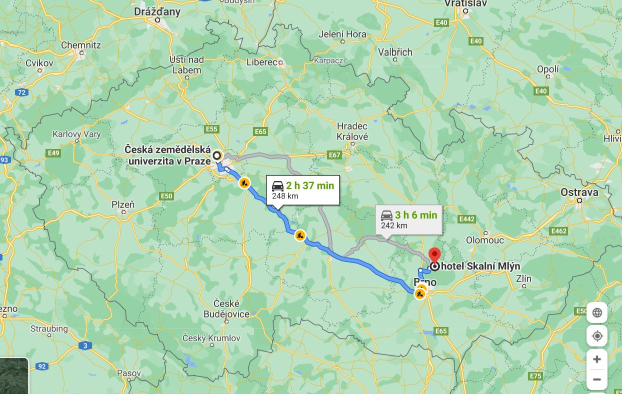

Route from the University campus to the Moravian Karst (Skalní Mlýn, Blansko)

Route from the University campus to the Moravian Karst (Skalní Mlýn, Blansko)

Source: Googlemaps https://google.com/maps

Let's start our excursion in this special karst landscape and protected nature reserve.

The excursion starts on the University campus, where we meet in the very early morning and leave together by bus. The ride takes at least 3 hours, but if there is heavy traffic or some construction works on the motorway, it can take much longer. That is why meet as early as 5 a.m. on the University campus.

When we reach Skalní Mlýn (parking lot and information center), we buy tickets to our first stop in Punkva Cave system.

There are several stops within the area to explore and get familiar with the uniqueness of the area

1.

After a short walk, we enter the Punkva Cave system (at a given time) and we visit the beutifully decorated Domes, Macocha Abbys and if there is enough water, we also take a boat tour on the underground River Punkva.

2.

Then we walk back to Skalní Mlýn, where usually our Guide, ranger from the PLA Administration Moravský kras, joins our group and and guides us through the rest of the excursion. We walk to the very top of the Macocha Abbys to see the depth of 138 m, where the bottom of the Abbys is located.

3.

Then our excursion continues to Sloup, where we visit the Sloup and Šošůvka caving system with the Kůlna Cave, which is noted for its Paleolithic and Mesolithic material and evidence of human presence.

4. After that our excursion heads back to Skalní Mlýn, to the Moravian Karst House of Nature. We enjoy a short 3D movie about the area and can also enter its expositions.

5.

Our last excursion stop is in Holštějn, where the ruins of the Holštejn castle can be found together with the cave Lidomorna, which used to serve as prison.

6.

Before we go back to the bus and go home, we make a final stop in a local country style restaurant to have some meal. As you could see from our plan, there are not many options to buy food and beverages. It is more convenient to take the supplies for the day with you. Depending on the situation, we usually leave Holštejn between 7 and 8 p.m. That means a late arrival, between 10 and 11 p.m.

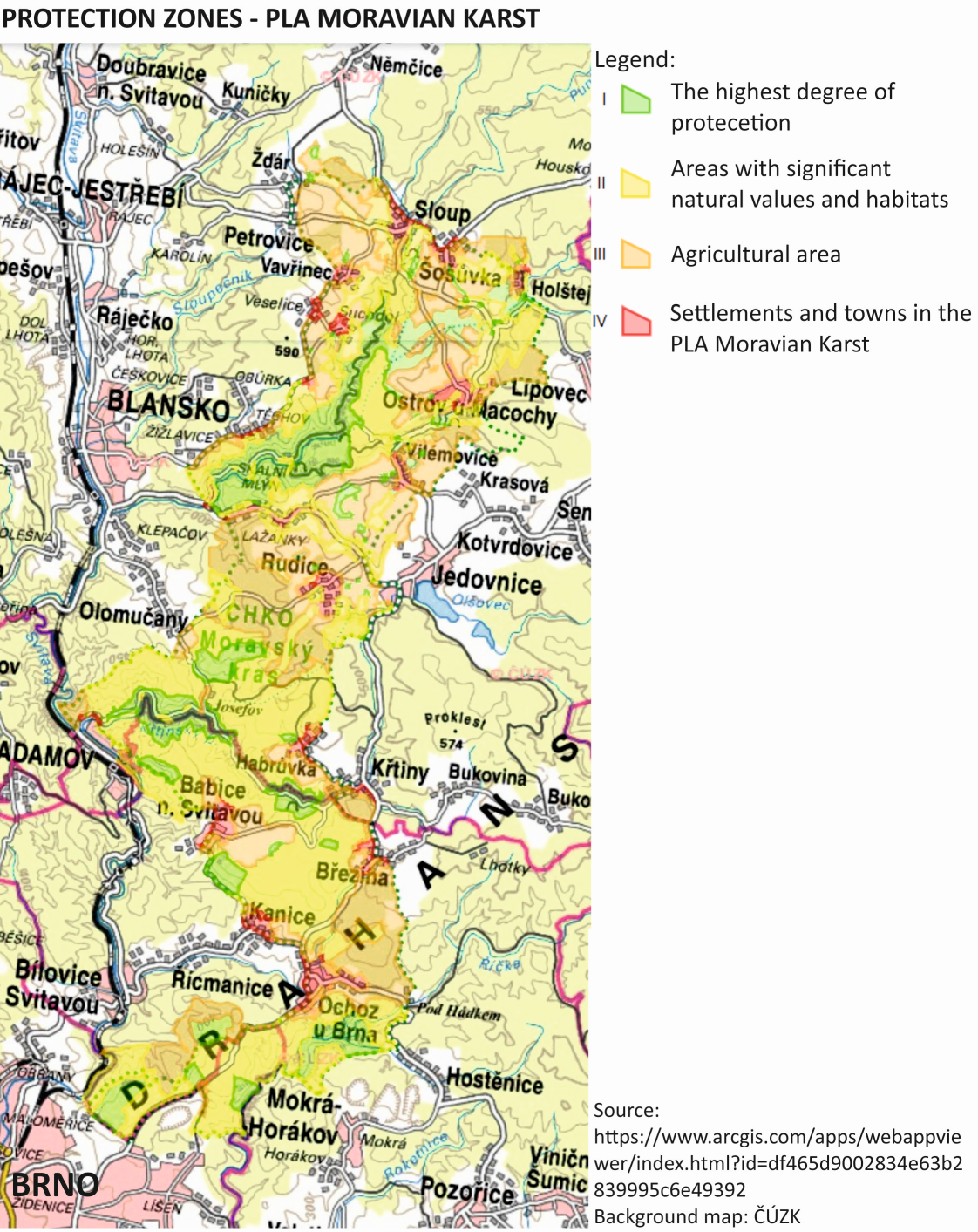

Protected Landscape Area (PLA) since 1956 (Ministry of Education order from 4th July 1956, No. 18.001/55).

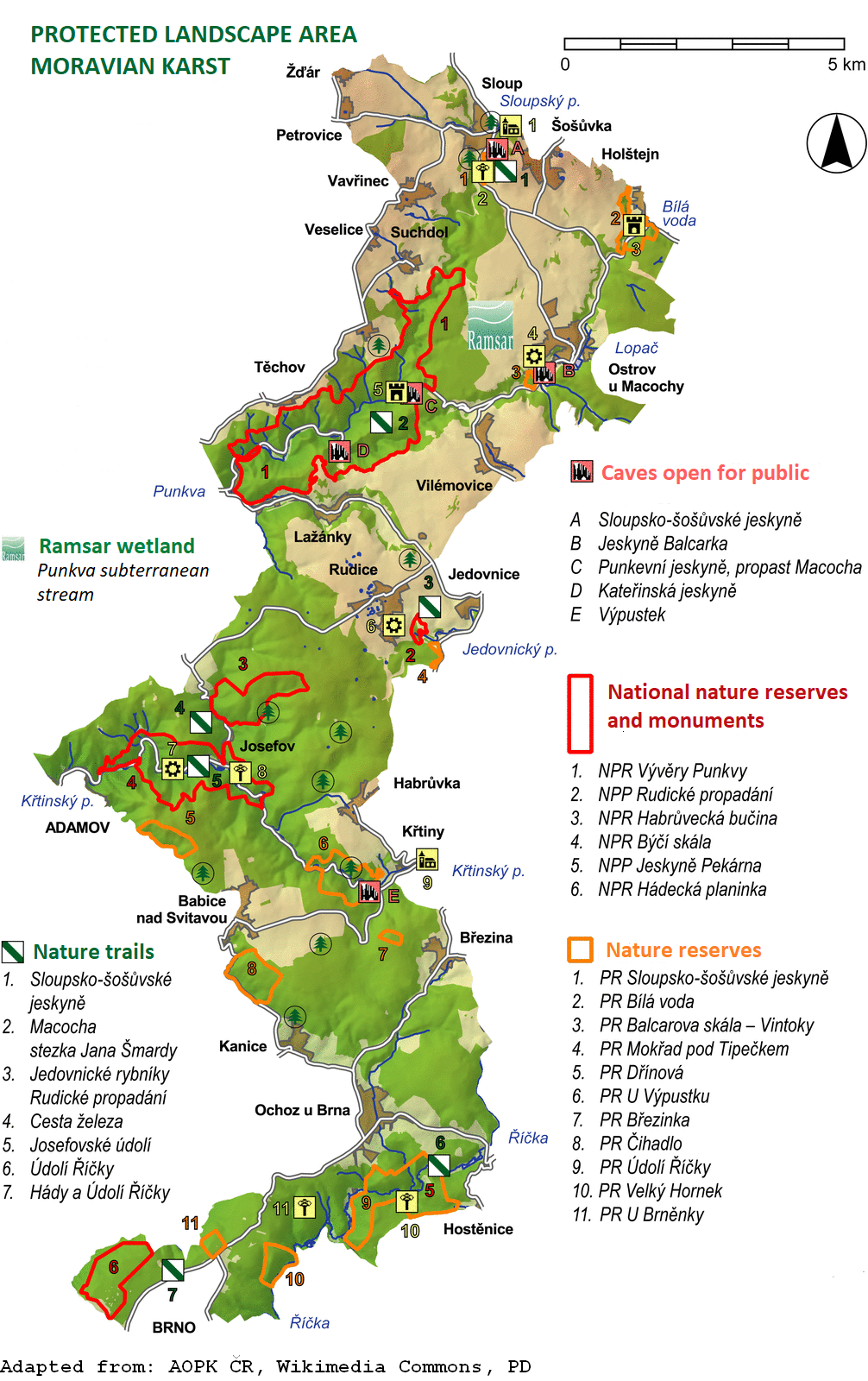

Extraordinary karst phenomena, precious fauna and flora on an area of 92 km² with more than 1 100 caverns and gorges. Within this area, several small-scale protected areas are specified: 4 National nature reserves, 2 National nature monuments and 11 Nature reserves. Červený kopec and Stránská skála national nature monuments (lying outside the PLA) are also administrated by the Administration of Moravský kras PLA.

Location: 49°13´ - 49°25´ N, 16°39´ - 16°47´ E

Location: 49°13´ - 49°25´ N, 16°39´ - 16°47´ E

Altitude: 220 m (Říčka stream) - 610 m (Helišova rock)

It is one of the most important karstic areas in Central Europe. Four systems of caves are open for public:

–Punkva Caves including Macocha Abyss/Chasm and boat trip through the caves system (4750 m in length)

–Katerinska Caves with unique decoration of stalagmites (950 m in length)

–Balcarka Caves with colorful stalactical decoration (1150 m in length)

–Sloup and Šošůvka Caves with the large galleries and internal underground chasms (4890 m in length)

–Macocha Abyss is 138 m deep, there are two lakes, upper one is 13 m deep, in lower one the depth is not known yet, the measurements were performed to 49 m only

–The River Punkva flows through the bottom of Macocha Chasm and in the lower lake it enters the underground system through Punkva Caves

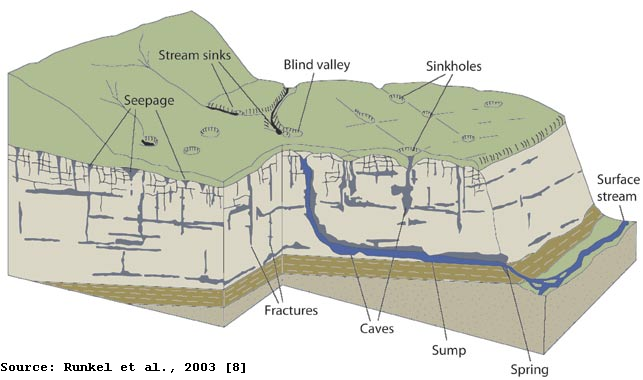

LANDSCAPE ATTRIBUTE

Moravský Kras is the largest karst area in the Czech Republic. The karst area consists of Devon limestone lying northward from Brno. The landscape character is formed by plateaus with many sinkholes separated by deep canyon grooves. Most of the water flow coming from the non-karst parts of the Drahanská uplands vanishes underground where the limestone area begins. The water-flow created various cave labyrinths here during the long geological evolution. The northern part of Moravský Kras is drained by the Punkva River and its tributaries. The Amatérská Cave complex is to be found here, stretching for almost 35 km when contiguous caves are included, making it one of the largest cave systems in Europe. In the central part of Moravský Kras, Rudické sinking-Býčí rock is the main cave cave system, which is 12 km long. Ochozská Cave, 2 km long, is the most famous cave in the southern part of the area.

Moravský Kras is the largest karst area in the Czech Republic. The karst area consists of Devon limestone lying northward from Brno. The landscape character is formed by plateaus with many sinkholes separated by deep canyon grooves. Most of the water flow coming from the non-karst parts of the Drahanská uplands vanishes underground where the limestone area begins. The water-flow created various cave labyrinths here during the long geological evolution. The northern part of Moravský Kras is drained by the Punkva River and its tributaries. The Amatérská Cave complex is to be found here, stretching for almost 35 km when contiguous caves are included, making it one of the largest cave systems in Europe. In the central part of Moravský Kras, Rudické sinking-Býčí rock is the main cave cave system, which is 12 km long. Ochozská Cave, 2 km long, is the most famous cave in the southern part of the area.

In total, there are more than 1100 caves in Moravský Kras. In most of them, traces of ancient life and social development have been conserved. Inside Kůlna Cave there is evidence of the most ancient settlement ever discovered in Moravský Kras - that of a Neanderthal man 120000 years ago. Discoveries of engravings of horses and bison in Pekárna Cave are also remarkable. They were made by horse and reindeer hunters and they are estimated to be from 11000 to 13000 years old. The caves are also the main tourism attraction. About 400000 people visit them every year. Unique fauna and flora occur here due to the bedrock, broken terrain and the location on the border between the Panonian and Hercynian biogeographical regions. Cave fauna is remarkable. The most famous are bats, of which 23 species have been discovered till now. There are also numerous invertebrates living in the Moravský Kras caves that are perfectly adapted to life in total darkness. Some new, previously unknown species have been found here. As for critically endangered plants, Cortusa matthioli (Matthioli’s cortuse), a glacial relict, grows on Macocha gorge rock wall. The structure of forests is mostly indigenous and they cover almost 60% of the area.

Cortusa matthioli is a herbaceous plant of the Primulacea family, widespread in the mountains of Central and Southeastern Europe and the European part of Russia. Related (and similar) species grow in the mountains of Central and East Asia. It grows on shady wet limestone rocks e.g. in the Alps or Carpathians. In the Czech Republic it occurs in a single location of a special character – on the walls of the lower part of the Macocha Abyss. It was preserved here as a relict (remnant) from the end of the last Ice Age. Macocha plants are considered an endemic subspecies by botany. In the mountains in our country, Cortusa matthioli does not grow, because there is no limestone bedrock at higher altitudes of the Czech mountains.

Cortusa matthioli is a herbaceous plant of the Primulacea family, widespread in the mountains of Central and Southeastern Europe and the European part of Russia. Related (and similar) species grow in the mountains of Central and East Asia. It grows on shady wet limestone rocks e.g. in the Alps or Carpathians. In the Czech Republic it occurs in a single location of a special character – on the walls of the lower part of the Macocha Abyss. It was preserved here as a relict (remnant) from the end of the last Ice Age. Macocha plants are considered an endemic subspecies by botany. In the mountains in our country, Cortusa matthioli does not grow, because there is no limestone bedrock at higher altitudes of the Czech mountains.

GEOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE AREA (description based on Cave Administration of the Czech Republic [1])

The Moravian Karst is formed by limestones of Middle to Late Devonian age (350 – 380 million of years ago). These sea sediments (organogenous type) form the Josefov, Lažánky, Vilémovice and Křtiny formations of limestones. Their total thickness is estimated to be between 500 and 1000 m. In the West they lie on old deep-mined volcanic rocks (granodiorites of the Brno Massif). In the East they are overlapped by Culm greywackes and shales of Carboniferous Age. After the Palaeozoic Sea dereliction and mighty Variscan folding which hit the whole Bohemian Massif, the limestones began to undergo intensive karstification. Karstification can be described as a product of two mechanisms: the flow of water into the carbonate rock, and the dissolution of carbonates by acidic water. During the Mesozoic and Tertiary eras, it was again interrupted by short-term sea floods, which reflected orogenic unrest of the main phases of mighty Alpine folding. The Mesozoic Sea then left its carbonate sediments with fossils of ammonites, belemnites, and other sea animals, for example, in the surroundings of Olomučany. Varicoloured layers of kaolinitic sands and clays filling deep karst pockets (so-called sand pipes) survived from the Early Cretaceous Period in the surroundings of the village of Rudice. It is a residue of intensive weathering processes from the time when a tropical climate dominated there. The following development of the Moravian Karst was influenced by the Badenian sea flooding in the Tertiary. Deep karst canyons with the oldest cave systems at that time were filled with young clay sediments, which basically changed the hydrographic development of the Moravian Karst. From the Middle Tertiary, the Moravian Karst gradually changed to the present form.

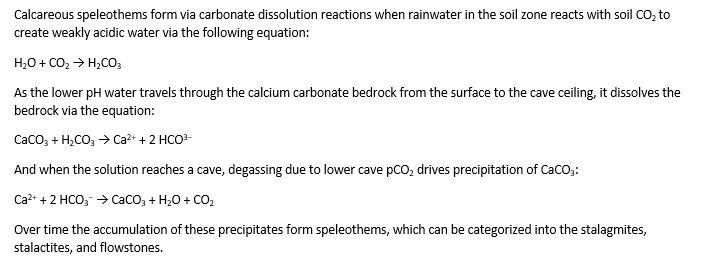

KARSTIFICATION PROCESS

Encyclopedia of the Environment [2] employs the term "karstification potential" which is formed by the two karstification mechanisms (the flow of water into the carbonate rock and the dissolution of carbonates by acidic water). The karstification potential is defined by two factors: the “engine” of groundwater flow and the “solvent”, which allows the dissolution of the rock by groundwater. In general, about 1 mm3 of speleothem grows every 15 years.

Wikipedia refers to more than 300 variations of cave mineral deposits, most of which are composed of calcium carbonate in the form of calcite or aragonite, or calcium sulfate in the form of gypsum.

S

S

PUNKVA CAVES AND MACOCHA ABYSS

Punkva Caves are part of the longest cave system in the Czech Republic – the Amateur Caves. The caves were discovered in stages in the years 1909–1933 by Professor Absolon’s group of speleologists. The main entrance is about 2 km distant from Skalní mlýn – in Pustý žleb under the vertical cliff. The tour startswith a walk through a number of chambers with a beautiful stalactite and stalagmite ornamentation, leading to the very bottom of the Macocha Abyss (138.7 m deep), and is followed by a water cruise on the underground River Punkva. The Abyss is characterized by its specific microclimate. Thanks to the chilliness and high humidity, several varieties of highland plants and invertebrate animals can be seen there. From the outside, the depth of the Macocha Abyss can be viewed from two observation platforms. The upper observation platform at a height of 138 meters above the bottom of the Abyss, and the lower observation platform at a height of around 90 meters from the bottom. The exploration of the Abyss has a rich history; the first documented descent to its bottom is dated to 1723.

Punkva Caves are part of the longest cave system in the Czech Republic – the Amateur Caves. The caves were discovered in stages in the years 1909–1933 by Professor Absolon’s group of speleologists. The main entrance is about 2 km distant from Skalní mlýn – in Pustý žleb under the vertical cliff. The tour startswith a walk through a number of chambers with a beautiful stalactite and stalagmite ornamentation, leading to the very bottom of the Macocha Abyss (138.7 m deep), and is followed by a water cruise on the underground River Punkva. The Abyss is characterized by its specific microclimate. Thanks to the chilliness and high humidity, several varieties of highland plants and invertebrate animals can be seen there. From the outside, the depth of the Macocha Abyss can be viewed from two observation platforms. The upper observation platform at a height of 138 meters above the bottom of the Abyss, and the lower observation platform at a height of around 90 meters from the bottom. The exploration of the Abyss has a rich history; the first documented descent to its bottom is dated to 1723.

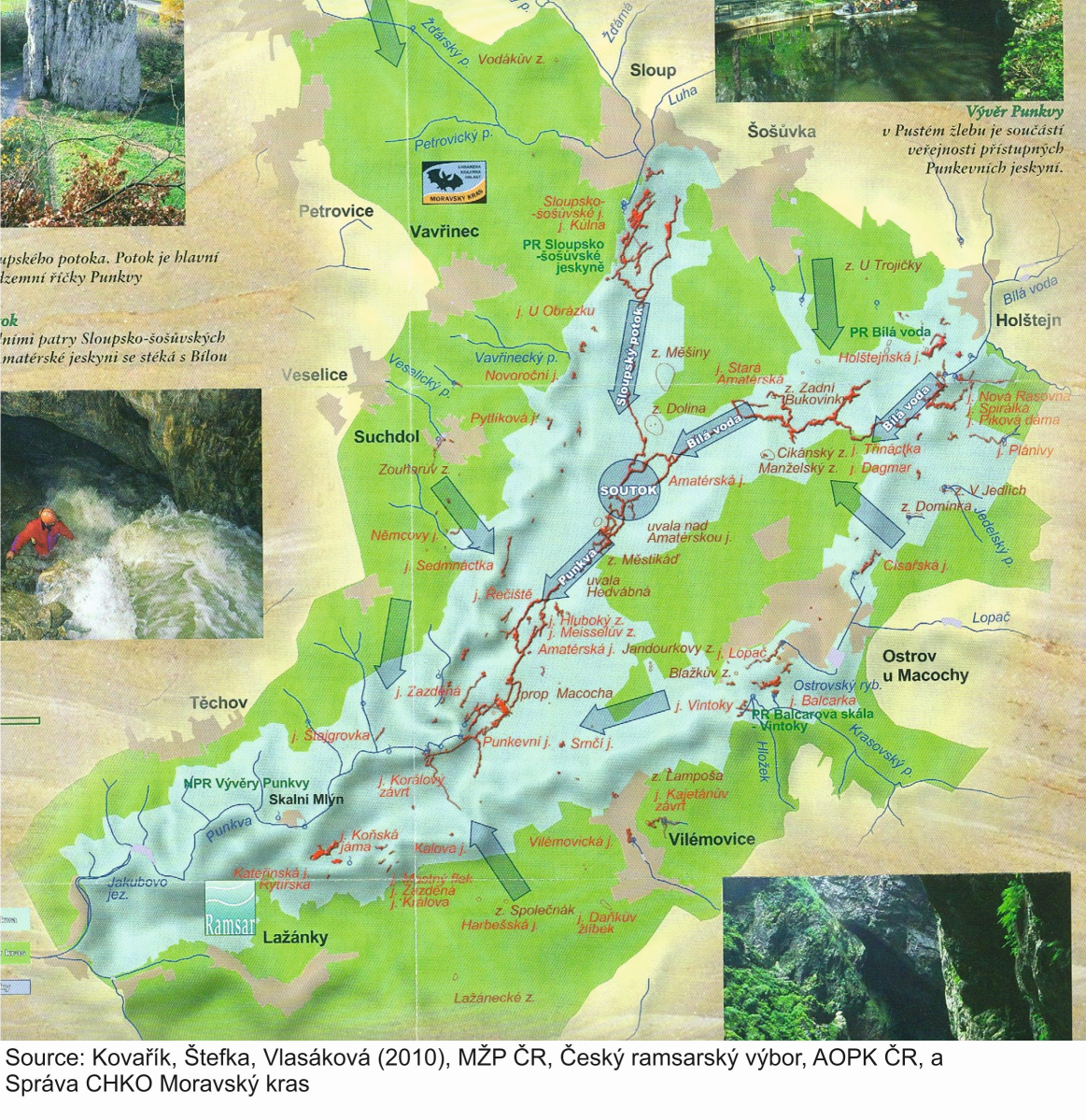

Subterranean Stream Punkva Translation: Potok (p.) = Brook; Soutok = Confluence; Jeskyně (j.) = Cave; Závrt (z.) = Sinkhole; Propast (prop.) = Abyss/Chasm; Blue tributaries – surface water; Red tributaries – underground water

Subterranean Stream Punkva Translation: Potok (p.) = Brook; Soutok = Confluence; Jeskyně (j.) = Cave; Závrt (z.) = Sinkhole; Propast (prop.) = Abyss/Chasm; Blue tributaries – surface water; Red tributaries – underground water

As described in Ramsar Information Sheet [3] the hydrography and hydrology of this karst area is rather complicated and not yet fully understood. It has its own, mainly subterranean hydrographic system with the Punkva Stream as the erosion base. Sloupský potok and Bílá voda streams are the sources for the Punkva Stream, that has a catchment area of 170 km2 and average discharge of 0.96 m3/s. The function of some sinks and springs depend on the water dynamics - subterranean streams cross each other at different levels and a sink may become a spring and vice versa. Surface streams are almost non-existent, subterranean streams and their catchments do not correspond with the surface relief.

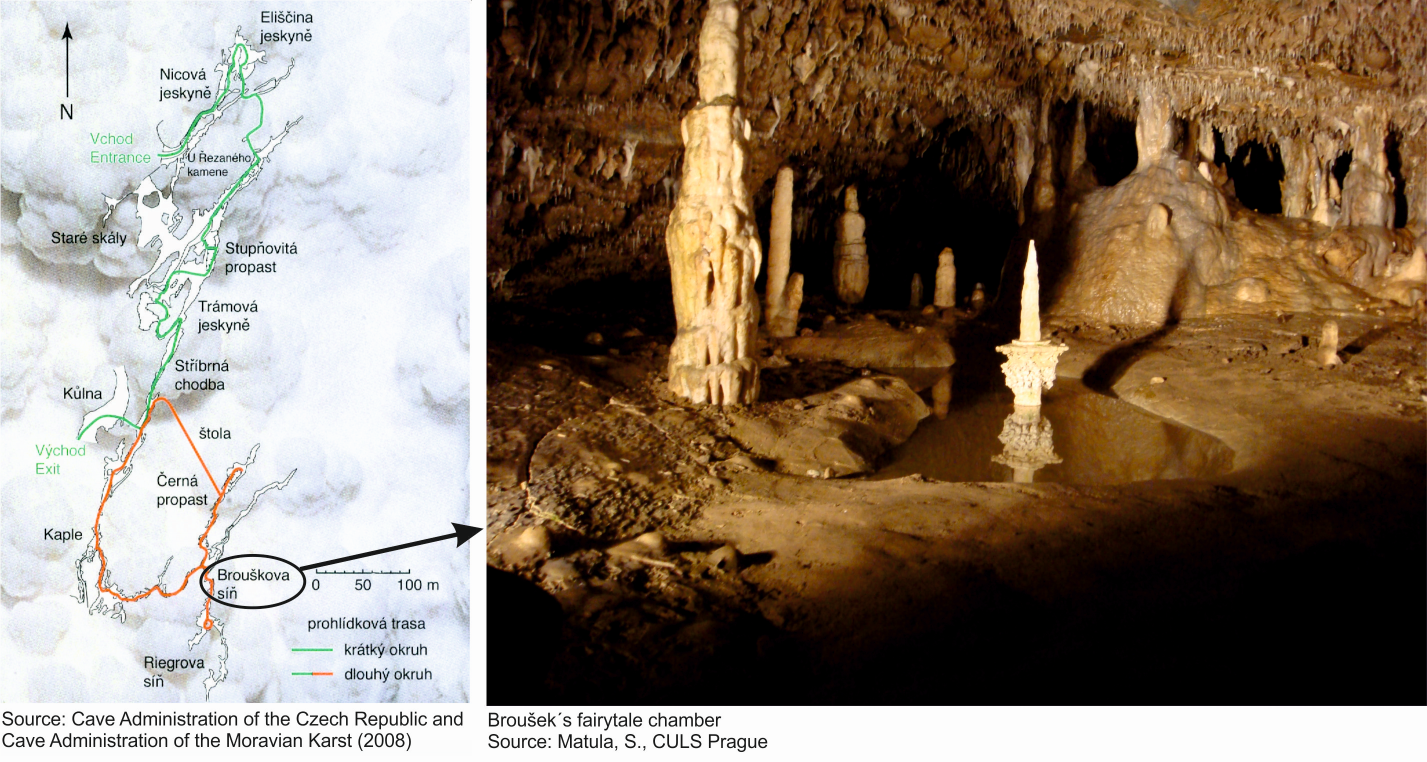

SLOUP - ŠOŠŮVKA CAVES

A large and complicated complex of underground domes, corridors and chasms on two levels (floors). It is an important place where cave animal carcasses have been found.  The greatest underground abyss of this type in the Czech Republic - the 80 m deep Nagel Chasm can be observed from the two platform-bridges. In addition to rich stalactite decoration, there is an excellent acoustics in Eliška´s Cave. Šošůvka´s part was discovered at the beginning of 20th century and is characterized by fragile and color stalactite and stalagmite decoration.

The greatest underground abyss of this type in the Czech Republic - the 80 m deep Nagel Chasm can be observed from the two platform-bridges. In addition to rich stalactite decoration, there is an excellent acoustics in Eliška´s Cave. Šošůvka´s part was discovered at the beginning of 20th century and is characterized by fragile and color stalactite and stalagmite decoration.

A significant archeological locality - Kůlna Cave - is part of the sightseeing tour open for public.

HUMANS IN MORAVIAN KARST

In most of the caves, traces of ancient life and social development have been conserved. Inside Kůlna Cave there is evidence of the most ancient settlement ever discovered in Moravský Kras, that of Neanderthal man 120000 years ago. Discoveries of engravings of horses and bison in Pekárna cave are also remarkable. They were made by horse and reindeer hunters and they are estimated to be from 11000 to 13000 years old.

In most of the caves, traces of ancient life and social development have been conserved. Inside Kůlna Cave there is evidence of the most ancient settlement ever discovered in Moravský Kras, that of Neanderthal man 120000 years ago. Discoveries of engravings of horses and bison in Pekárna cave are also remarkable. They were made by horse and reindeer hunters and they are estimated to be from 11000 to 13000 years old.

WATER MANAGEMENT PROBLEMS OF KARSTIC AREAS

The surface is dry, easily drained by underground cavities. Groundwater table is deep and quickly sinks down after wet periods. Groundwater circulation is rapid and the risk of groundwater pollution is extremely high.

Parise et al. [4] described karst as an

extremely fragile natural environment with

a delicate equilibrium of karst ecosystems which can be dramatically and irreversibly changed by natural and/or anthropogenic processes.

Parise et al. [4] described karst as an

extremely fragile natural environment with

a delicate equilibrium of karst ecosystems which can be dramatically and irreversibly changed by natural and/or anthropogenic processes.

Hubelova et al. [5] studied influence of human activity on surface water quality in Moravian karst and described water as a key

factor in the formation and occurrence of karst

phenomena. Importance of surface water quality coming from the non-protected areas are highlighted.

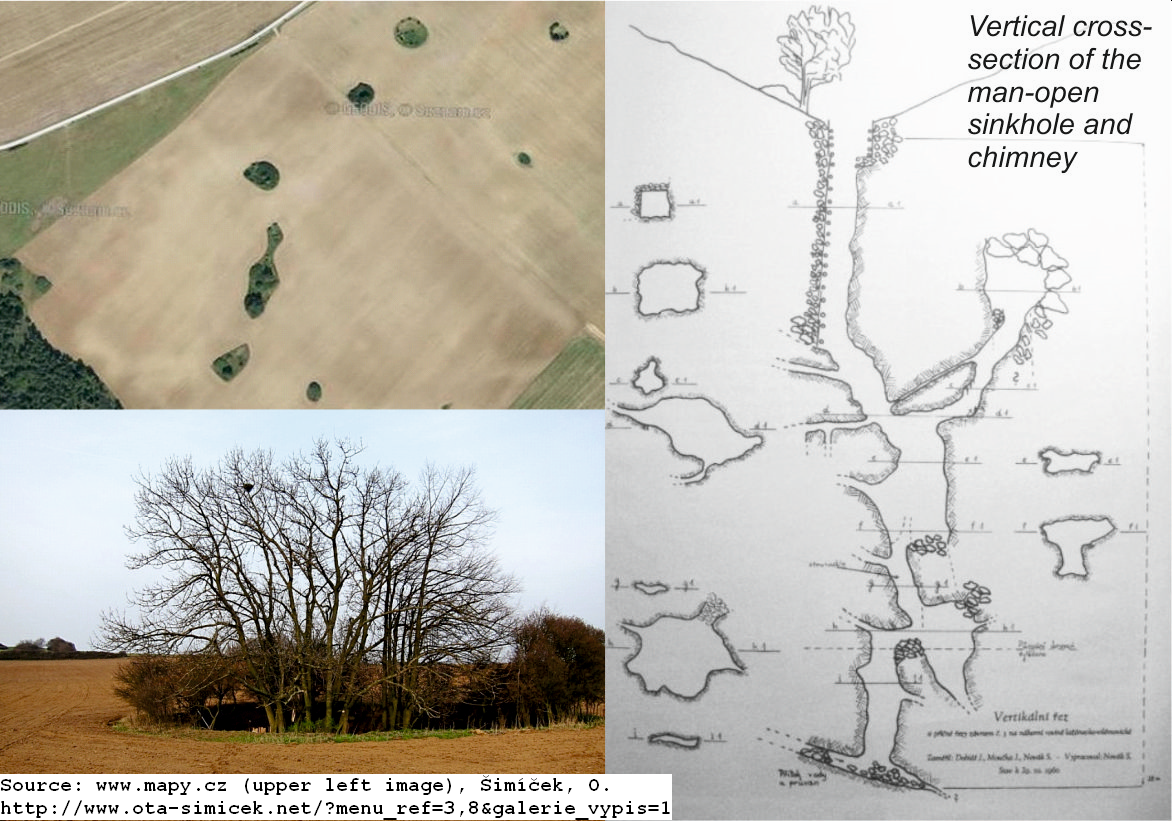

SINKOHLES IN THE MORAVIAN KARST

The sinkholes are typical for the landscape of karstic area.

Due to the progressing of the karstification processes and caves formations underground, a surface layer collapses eventually and a depression or hole in the ground is formed. Borders of sinkholes, chasms and other holes should be regarded as buffer zones around water sources. Arable agriculture, fertilizers and pesticides should be limited. Adequate erosion control measures are needed. Sinkholes filled with waste should be cleaned up if necessary.

Due to the progressing of the karstification processes and caves formations underground, a surface layer collapses eventually and a depression or hole in the ground is formed. Borders of sinkholes, chasms and other holes should be regarded as buffer zones around water sources. Arable agriculture, fertilizers and pesticides should be limited. Adequate erosion control measures are needed. Sinkholes filled with waste should be cleaned up if necessary.

WATER RESOURCES PROTECTION

The protection is based on observation of the following management practices:

Good sewerage; the supply of polluted water to the karst system is gradually eliminated by the construction of a network of wastewater treatment plants.

Good sewerage; the supply of polluted water to the karst system is gradually eliminated by the construction of a network of wastewater treatment plants.

Wastewater

treatment capable of removing N and P (placed outside the karst

if possible)

Surface

runoff from roads safely drained and contained

Surface

water reservoirs (dams, fishponds) avoided if possible

Water

quantity and quality monitored

Water abstraction and offtake

should be conservative

Using the grass belts around the sinkholes together with other adaptive measures in agricultural management

Effective protection of the karst is related to the regulation of limestone mining and reclamation of excavated quarries

It is forbidden to place and permit new constructions within the Protection Zone I. (routine maintenance can be performed on existing constructions). In other zones (II. and III.), constructions or measures can be implemented only in accordance with the

nature of the area based on issued permission from the Administration of

PLA Moravian Karst. Also, permissions for speleological research,

inventories and surveys in caves are issued by the State Nature Conservancy

bodies, such as Administration of the PLA and Administration of the National

Park.

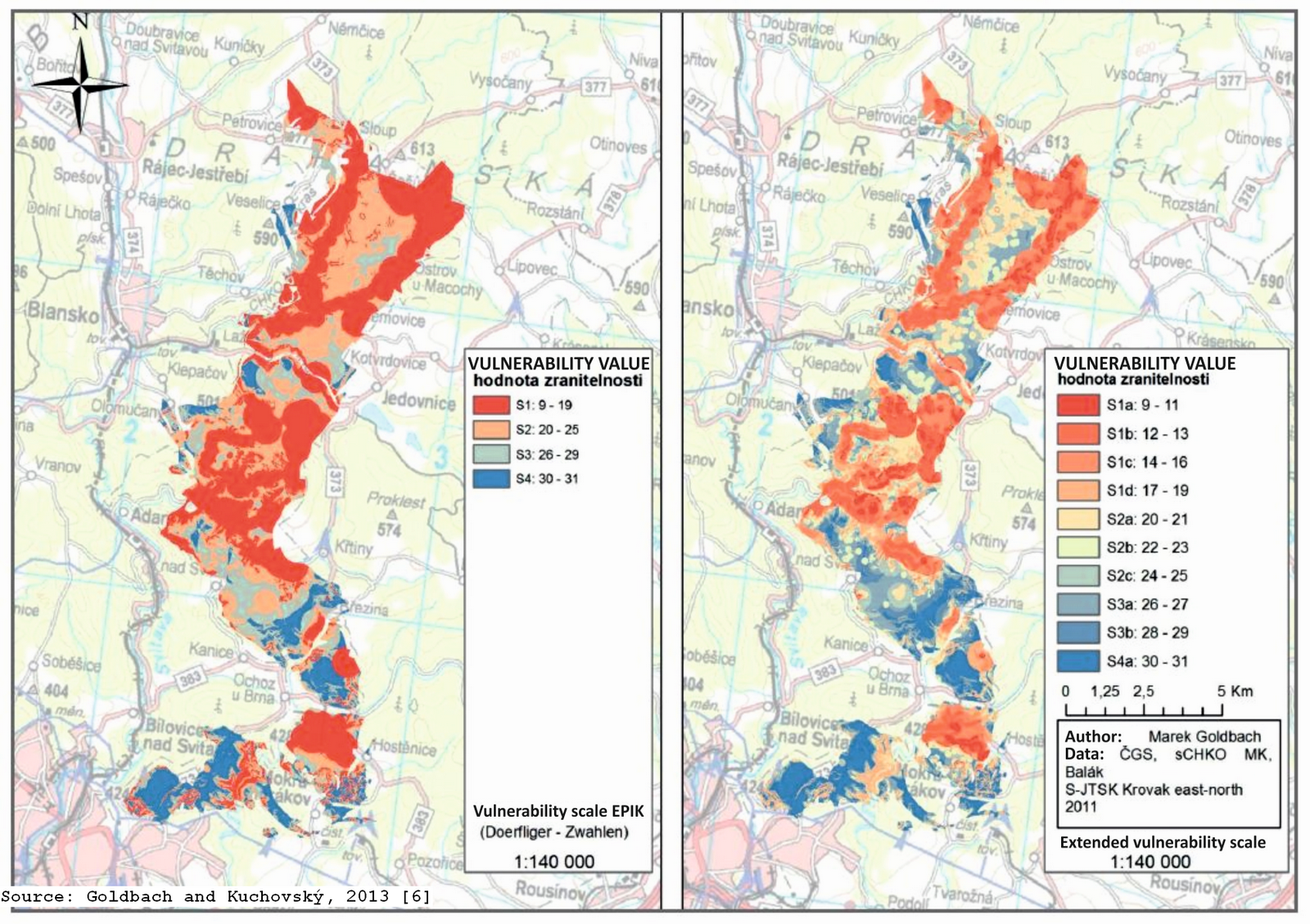

VULNERABILITY EVALUATION OF KARSTIC AQUIFERS (description based on Goldbach and Kuchovský, 2013 [6]]

Geographic Information Systems offer a number of possibilities to assess the aquifer vulnerability. Several methods were developed and applied, many of these have been replaced over time. To this day, the most often used method is the Multiparameter Method proposed by Aller et al. [7]; the DRASTIC method. Although it is a widely used method in practice, in karst areas it is incapable of capturing the specifics of groundwater flow and shows significant shortcomings in the results. Therefore,

the EPIK method was derived for karst areas by Doerflinger and Zwahlen [9]. The principle of the EPIK method is a relative quantification of4 basic characteristics of karst rocks and overlying cover layers that are relevant for the vulnerability assessment. Each of the parameters has a specific weight in the calculation of vulnerability. The higher the EPIC score, the lower vulnerability of the aquifer.

The E attribute describes the EPIKARST. Also, the distance from the sinkhole or other epikarst

phenomena together with the slope of the terrain are taken into account as important

factors.

The E attribute describes the EPIKARST. Also, the distance from the sinkhole or other epikarst

phenomena together with the slope of the terrain are taken into account as important

factors.

The P attribute describes the PROTECTION LAYER. The map of the thickness of the land cover would be the best data source.

The I attribute describes the INFILTRATION CONDITIONS. This can be determined by the land use data using GIS

("Land use") in combination with slope and information

on the sinking of surface water into groundwater.

The K attribute defines the development of the KARST NETWORK . The plans of caves, information

about the position and nature of the sinkholes or different sets of structural measurements from caves serve as input data.

Also, the degree of development and distance to these places are considered.

As a result of this study, a more detailed scale for the vulnerability evaluation has been suggested. Goldbach and Kuchovský [6] also reported that the EPIK method is not suitable

to assess the risk of a particular site for the possible

groundwater exploitation. The biggest shortcoming was found as; not-respecting of the directions of the groundwater flow in the karst aquifer. Therefore, it can be considered primarily as an effective protective tool to protect the collector as a whole, not for

assessment of the possibility of endangering a specific place of exploitation

groundwater. For this reason, the application of this method is not suitable for the correction of existing and/or newly planned hygienic protection zones of groundwater resources.

REFERENCES:

Collection of photographs showing the most important from the excursion.

Source: Matula, S., CULS Prague

Source: Matula, S., CULS Prague

Source: Matua, S., Miháliková, M., Báťková, K., CULS Prague

Source: Matula, S., CULS Prague

Source: Miháliková, M., CULS Prague

Source: Báťková, K., CULS Prague

Source: Matula, S, CULS Prague

Source: Matula, S., CULS Prague

Source: Matula, S., CULS Prague

Source: Matula, S., CULS Prague

Source: Matula, S., CULS Prague

Source: Matula, S., CULS Prague

Source: Matula, S., CULS Prague

Some historical photos from Amatérská Cave can be found on iDNES newspaper web page and historical photographs of the Macocha Abyss can be displayed on the historical photos web page.

Collection of photographs from the excursions in 2011-a and 2011-b.

Collection of photographs from different parts of Moravian Karst on Wikimedia Commons can be found here.

Amazing 5-minutes-video from the boat trip within the Punkva Caves can be displayed here.

Interesting 4-minutes-video from Sloup-Šošůvka Caves and surrounding (in Czech) can be displayed here.

Interesting, almost 12-minutes-long video from Balcarka Cave (no comments) can be displayed here.

Relevant on-line available papers and other relevant data

Different types of cave formations, their description and photographs on Wikipedia webpage can be displayed here

Bosák, P. (2003) Karst processes from the beginning to the end: How can they be dated? Speleogenesis and Evolution of Karst Aquifers 1 (3) - available here

Mechanisms of karstification on Encyclopedia of the Environment webpage https://www.encyclopedie-environnement.org

Hladil, J. (2003) The Post-Symposium Field Trip B-2: DEVONIAN AND CARBONIFEROUS OF THE MORAVIAN KARST (CZECH REPUBLIC) - available here

Bahik, I., Janeo J., Stefka, L., Bosak, P. (1999)

Agriculture and nature conservation in the Moravian karst (Czech Republic). Int.

J. Speleol. 28 B (1/4)1999:71

– 88 – available here

Vymyslický T., Musil Z. (2014) Monitoring of Vegetation Changes in

Selected Sinkholes in the Moravian Karst, Czech Republic. In: Sokolović

D., Huyghe C., Radović J. (eds) Quantitative Traits Breeding for

Multifunctional Grasslands and Turf. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9044-4_5

Šamalikova, M. Engineering-Geological

Problems in the Moravian Karst, Czech Republic - can be displayed here

Munk, E. (2011), Ancient cave in the Moravian karst still

stumps archaeologists. The Prague Post (October 26, 2011) – available here

ČTK (2020) Oldest

Czech cave painting 800 years older than previously believed (updated on 21.05.

2020) – available here

Ramsar Information Sheet (March 2004)- Ramsar Site: 1413-Punkva

subterranean stream – available here

Parise M. et al. (2015) Hazards in Karst and Managing Water

Resources Quality. In: Stevanović Z. (eds) Karst Aquifers—Characterization and

Engineering. Professional Practice in Earth Sciences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-12850-4_17

Vogelbacher, A.; Kazakis, N.; Voudouris, K.; Bold, S. (2019) Groundwater Vulnerability and Risk Assessment in A Karst Aquifer of Greece

Using EPIK Method. Environments 6(11), 116. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments6110116

Hubelova, D., Mala, J., Kozumplikova, A., Schrimpelova, K., Hornova, H., and Janal, P. (2020). Influence of Human Activity on Surface Water Quality in Moravian Karst. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies, 29(5), pp.3153-3162. https://doi.org/10.15244/pjoes/114233

Gregor, V. A., The Moravian Karst – The Jedovnice Creek cave

system of the Rudice Plateau in the Moravian Karst – the Rudice Swallow Hole,

Bull Rock and Bar caves – available here

Pohanka, V. (2018) Moravian Karst - Natural Wonder of

Moravia available

able here

Karst and sinkholes on the webpage of University of Wisconsin - Madison (Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey) - available here

created with

Website Builder Software .